Difference between revisions of "Using CoGe for the analysis of Plasmodium spp"

(→About this Guide) |

(→About this Guide) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

* CoGeBLAST: Blast against any set of genomes | * CoGeBLAST: Blast against any set of genomes | ||

* GEvo: Microsynteny analysis | * GEvo: Microsynteny analysis | ||

| − | * SynMap: Whole genome analysis | + | * SynMap: Whole genome syntenic analysis |

:- Kn/Ks analysis: characterize the evolution of populations of genes | :- Kn/Ks analysis: characterize the evolution of populations of genes | ||

:- SPA tool: Syntenic Path Assembly to assist in genome analysis | :- SPA tool: Syntenic Path Assembly to assist in genome analysis | ||

Revision as of 15:34, 21 November 2016

Contents

- 1 About this Guide

- 2 A brief introduction to Plasmodium genome evolution

- 3 Finding and importing data into CoGe

- 4 Using CoGe tools to perform comparative analyses

- 4.1 Analyzing GC content and other genomic properties (GenomeList)

- 4.2 Identifying gene homologs (CoGeBlast)

- 4.3 Identifying microsyntenic regions (GEvo)

- 4.4 Performing syntenic analyses between two genomes (SynMap)

- 4.5 Measuring Kn/Ks values between genomes (SynMap - CodeML analysis tool)

- 4.6 Identifying sets of syntenic genes amongst several genomes (SynFind)

- 4.7 Identifying codon and amino acid substitution frequencies (CodeOn)

- 4.8 Using Syntenic Path Assembly (SPA) to make analysis of poor or early genome assemblies easier (SynMap - SPA tool)

- 5 Overall conclusions

- 6 Useful links

- 7 References

About this Guide

Welcome to the Plasmodium genus genome analysis with CoGe guide. This 'cookbook' style document is meant to provide an introduction to many of our tools and services, and is structured around a case study of investigating genome evolution of the malaria-causing Plasmodium spp. The small size and unique features of this pathogen's genome make it a great example for beginning to understand how our tools can be used to conduct comparative genomic analyses and uncover meaningful discoveries.

Through a number of guided examples, this guide will teach users how to use the following tools:

- LoadGenome: Add a new genome to CoGe

- LoadAnnotation: Add structural annotations to a genome

- GenomeInfo: Get information about a genome

- GenomeList: Get information about several genomes

- CoGeBLAST: Blast against any set of genomes

- GEvo: Microsynteny analysis

- SynMap: Whole genome syntenic analysis

- - Kn/Ks analysis: characterize the evolution of populations of genes

- - SPA tool: Syntenic Path Assembly to assist in genome analysis

- SynFind: Identify syntenic genes across multiple genomes

- CodeOn: Characterize patterns of codon and animo acid evolution in coding sequence

A brief introduction to Plasmodium genome evolution

The unique features found in many parasitic genomes create unique challenges when using comparative genomics to study their evolution. Parasite genomes are characterized by a mixture of genome reduction associated with gene loss (e.g. homeobox genes), but also for the development of specialized genes. Many of the genes gained in parasitic genomes are involved in different aspects of host-parasite interaction and are, for the most part, species or lineage specific [1]. This dynamic nature of parasitic genomes is especially evident within the phylum Apicomplexa, and particularly within the genus Plasmodium. A marked loss of synteny between different Apicomplexa genera has been previously reported [2], although syntenic relationships between species within a single genus are largely conserved. While this finding remains true for many genera, the increasing number of sequenced Plasmodium genomes has shown that numerous clade and species-specific gain/loss events and chromosome rearrangements have occurred [3]. The exact origins and mechanisms of these rearrangements remains largely unexplored, but they are generally hypothesized to stem from different host shift events [4][5], which have led to diverse types of host-parasite interactions.

Despite the enormous diversity of Plasmodium parasites, all studies to date (2016) show conservation of certain genomic characteristics. Fourteen chromosomes, a mitochondrial, and an apicoplast compose the entire repertoire of the Plasmodium genome in all sequenced species. This conservation in genomic complement is remarkable, especially considering the potential for altering the number of chromosomes without compromising genome the size can be observed ancestrally (e.g. 4 chromosomes and 13Mb approximately in Babesia bovis vs. 14 chromosomes and 18Mb approximately in the smallest Plasmodium genome). As in the case of other parasites, Plasmodium genomes are relatively small (between 17-28Mb approximately) in comparison to those of the hosts, but larger than those of other Apicomplexan parasites (Theileria orientalis and Cryptosporidium parvum have genomes of approximately 9Mb) [6]. All Plasmodium species have a complex life cycle involving some kind of vertebrate host and a mosquito vector of the genus Anopheles. Though specificities and preferences during the infection process are prevalent within the genus [7], the overall preservation of the life cycle characteristics suggests the existence of a set of preserved core genes. These core genes represent are pivotal elements for the use of comparative genomics on the study of Plasmodium evolution.

An increase in funding devoted to malaria research during recent years has come hand in hand with increased understanding of Plasmodium genetics [8]. At the moment, there is an unprecedented amount of Plasmodium genomes and gene sequences publicly available, spread through diverse databases. The most prominent repository is found in NCBI/Genbank [9]; while additional and unique sequences can also be found on other databases: PlasmoDB, GeneDB and MalAvi [10][11][12]. The availability of genomic data from Plasmodium species opens the possibility to: identify the likely origin of certain traits, specialized phenotypes, and genomic landscapes; track the maintenance of conserved genes across the genus, as well as the rise and loss of genes unique to only a single or a group of closely related species; and infer the potential historical interactions which might have lead to the development of adaptations as well as their putative consequences.

One of the many remarkable trends of Plasmodium genome evolution is the rapid change in GC content. P. falciparum and closely related parasites have a remarkably AT rich genome compared to other Plasmodium species [13]. While significant shifts in GC content have been reported in other parts of the tree of life such as Bacteria [14][15] and monocots [16], the short evolutionary time during which this change has occurred in Plasmodium is noteworthy. Moreover, the GC content variability observed amongst Plasmodium species has not yet been observed in other Apicomplexan genera. AT rich genomes not only present challenges for sequencing [17], but they result in entirely different trends of codon and amino acid usage. Furthermore, patterns of genome mutability and in the evolution of repetitive elements can also be markedly different in AT rich genomes. By utilizing various analysis tools for comparative genomics, it is possible to assess the evolutionary origins and trace patterns of GC content shift across the Plasmodium genus.

Another important aspect in Plasmodium evolution is the unique patterns of genome variability and the diverse responses to numerous selective pressures observed in different Plasmodium genomes. In this regard, comparative analyses performed between Plasmodium species and strains can elucidate the key elements behind these differences (e.g. different hosts pressures or an earlier species split), as well as to identify genomic regions and elements where this type of change is more prominent. But perhaps more significantly in Plasmodium evolution, and in that of parasites in general [18], might be the origin and evolution of multigene families. Within the Plasmodium genome, numerous multigene families show specific tracks of gene gain/loss events, and can be associated to variable syntenic changes. Moreover, the differences in the ancestry of these families is also noteworthy, with many of them being observed only in a single Plasmodium species or those which are closely related, and others being observed across the entire genus but not in other Apicomplexa parasites [19]. In this sense, each multigene family can illustrate a different aspect of the evolutionary history of the genus.

In the following paper, we will demonstrate how to use the CoGe platform to analyze genomes and evaluate diverse evolutionary hypotheses. Through a case study on Plasmodium evolution, we will illustrate how CoGe can be used for the analysis of both genes (specifically multigene families) and whole genomes (genome composition, rearrangement events, conservation).

Finding and importing data into CoGe

The initial step in sequence analysis using CoGe is the import of new sequences to the platform.

The analysis of Plasmodium parasites using comparative genomics can be a challenging task due to the previously mentioned particularities of their genomes. Considering that an increasing number of Plasmodium genomes have become available in recent years, and that the genomic information for the genus is likely to increase in the near future, it is fundamental to search new alternatives for the incorporation, analysis, and visualization of Plasmodium genomic data. Particularly, tools which allow the rapid analysis of numerous sequences at various levels, and permit the identification of potentially relevant patterns to which novel analyses can be focused, are currently of high relevance for Plasmodium research. Additionally, the use of online platforms where complex genomic data can be incorporated and analyzed facilitate the start and continuation collaborative initiatives. In particular, these platforms allows for the analysis of data regardless on differences between operative system, geographic location, or even access to high performance equipment, an aspect of large significance in a genus like Plasmodium which in the case of humans causes diseases associated to developing tropical countries where access to some equipments and software can be reduced.

Finding about the Plasmodium genomes already present in CoGe

While the amount of Plasmodium genomic data has risen during the pass years, important advances in Plasmodium genomics have been occurring since the publication of the P. falciparum genome [20]. Thus, there is a prominent amount of historical data which can also be used for analysis, and depending of the hypotheses of interest, might be more relevant that later versions of the same data. As a result, there are a number of Plasmodium genomes under different development versions already imported into CoGe.

Before importing any genome into the CoGe database, and in order to prevent potential redundancy of genomic information, it is recommended to identify the Plasmodium genomic data already available (Figure 1). You can identify genomes by typing the word in "Plasmodium" into the Search bar at the top of most pages. This will retrieve all organisms and genomes with names matching the search term. Clicking on any of these organisms will allow you to see the details of the uploaded genome. Alternatively, you can explore the uploaded genomes by finding the Tools tile on the main CoGe page and clicking on to Organism View (https://genomevolution.org/coge/OrganismView.pl)

All publicly available genomes uploaded into CoGe and any corresponding information attached to them can be found in the Organism View section (Figure 2). You can find any published genome by typing a scientific name into the Search box. For each organism uploaded to CoGe you will find the following information (Figure 3):

- Organisms: In the case of Plasmodium spp., the different parasitic strains currently uploaded. Any organelle genomes independently uploaded (mitochondrial and apicoplast) can also be found in this section.

- Organism Information: provides an outline of the organisms’ taxonomy (following that published on NCBI/Genbank). This section also includes quick links to some of the main CoGe analysis tools and additional search engines.

- Genomes: All the genome versions for the species of interest. Note that by selecting different genome versions, all other genomic information associated to that species is modifies on site. This section allows you to access to previous versions of a published genome (e.g. access scaffolds from a previous genome version currently under the chromosome assemble level).

- Genome information: Shows the genome IDs, type of sequences uploaded and the length of these sequences. In this tab you will also be able to directly perform analyses using the CoGe platform.

- Datasets: This section shows the number of datasets included for the specified genome. In the case of completely sequenced Plasmodium genomes obtained from NCBI/GenBank, it will indicate the accession numbers for each individual chromosome.

- Dataset information: Provides specific information for each individually selected dataset including accession numbers (if available), source of the upload, chromosome length, and GC%.

- Chromosomes: Shows the number of available chromosome for the selected genome. However, depending of the method used to import the data into CoGe and the nature of the dataset itself, the count and length of chromosomes shown will be larger than expected (e.g. number of contigs in lieu of the number of chromosomes).

- Chromosome information: Shows the chromosome ID and the number of base pairs (bp) for that chromosome.

Clicking on the Genome Info section within the Genome Information section provides a more detailed description of the genome of interest and allows access to quick links to most comparative analysis tools available on CoGe. Keep in mind that only publicly available genomes imported to CoGe can have a Public or Restricted display. Genomes made public can be seen and analyzed by anyone using the CoGe platform. On the other hand, Restricted genomes can only be seen/analyzed by the user or those with whom the information has been shared with: Sharing_data

Importing Plasmodium genomes into CoGe

While data can be uploaded into CoGe using a variety of methods, we will focus on two of the most likely to be used in the incorporation of Plasmodium genomes. For additional information, please check the following link: How_to_load_genomes_into_CoGe. Depending on your interests and hypotheses, it might be necessary to perform analyses using complete Plasmodium genomes or to focus only in specific organelles and chromosomes. The methods described here can be used to upload either of these types of data:

- 1. Go to the genome database on NCBI/GenBank and type "Plasmodium" on the search box. You can select any genome of interest.

- 2. Find the Representative Genome section in the upper section of your screen. Below you will find the Download Sequences in FASTA format and Download Genome Annotation sections (Figure 4).

- - To download a complete P. vivax genome, click on Genome under Download Sequences in FASTA

- - To download a complete annotation for the P. vivax genome, click on GFF under Download Genome Annotation

- Alternatively, you can use the RefSeq and INSDC numbers for each chromosome and, if available, of the organelles.

- 3. Go to CoGe and login. You can follow this link: https://genomevolution.org/coge/

- 4. Click on the MyData section on the upper left part of the screen. This will lead to the Data section of your personal CoGe page (Figure 5). This section will fill up as genomes of interest are uploaded into CoGe.

- 5. On the upper left section of the screen, click the NEW button and select New Genome from the dropdown menu.

- 6. On the Create a New Genome window you will input information about the organisms' taxonomy and genome's origin must be entered (Figure 6). Keep in mind that depending on the type of organism being uploaded, taxonomic information might not have been incorporated into CoGe just yet (e.g. a private species of strain). If this is the case, make sure to create a new organism by following these steps:

- a. Click on NEW on the "Organism:" section

- b. On the Search NCBI box type the scientific name of the organism to be uploaded. If the organism of interest is not on NCBI yet, select its closest taxonomic relative. In the case of Plasmodium, several strains might be available for a given species (particularly P. vivax and P. falciparum), make sure to select the correct strain or, if a new strain is being uploaded, to add the new strain's name.

- c. Click Create

- 7. After successfully creating a new strain/genome, is time to include any additional information that might be needed in the future as well. Depending on the number of versions for the selected genome already available at CoGe, a different number will be typed on Version. Thus, it is important to check the latest genome version available on CoGe before importing a new version of the same genome (e.g. P. falciparum currently has 5 versions, so any new version incorporated should be numbered as version 6). Under the Type section, select the adequate sequence type from the drop down menu (most sequences can be identified as unmasked, Masked). Select the Source in the next dropdown menu (in this case the source is NCBI, but other databases as well as Private sources are also available). Finally, tick the check box if you desire your genome to be Restricted. Remember that:

- - Restricted genomes can only be seen and analyzed by the user and those with whom the genome has been shared.

- - Unrestricted genomes are available to anybody using CoGe.

- 8. Click Next

- 9. This new window allows you to import genome files by using four different strategies: first, data can be imported directly from the Cyverse Data Store (if the data is not already on the Data Store it can be easily imported from CoGe afterwards); second, creating an HTP/FTTP link directly to the data; third, Upload the data from a private computer, and fourth, importing the data using GenBank accession numbers.

- To import genomes using Upload:

- a. Select a genome file downloaded from your local computer and wait for it to be read by CoGe, once the process is completed select Next. Note that you should select a FASTA, FST or FAA file.

- b. Click Start on the next screen to begin the upload.

- c. Once the file upload has concluded all information included by the user, as well as any specifics regarding the FASTA file itself, will be visible in the Genome Information page. Note that genomes in earlier stages of assembly (e.g. Scaffolds) can be easily uploaded into CoGe by this method.

- To import genomes using NCBI/Genebank:

- a. Select the GenBank accession numbers option. Type or Copy/Paste the INSDC numbers for each Plasmodium chromosome (or for specific Plasmodium organelles) and click the Get button. Note that genomes can be uploaded one at the time using this method. Information from each imported genome should appear under Selected file(s). Once all genomes have been imported (14 chromosomes in the case of Plasmodium), click on the Next button.

- b. After the genome has been imported, all information included by the user, as well as any specifics regarding the genome FASTA file itself will be visible in the Genome Information page. Note that uploading chromosomes/genomes using this method also imports any information of genome annotation already included in NCBI/GenBank. Also note that genomes uploaded using this method will be unrestricted, and thus, visible to all CoGe users.

- c. At this point, genome annotation files can be also uploaded into CoGe for this genome. These files can be included by clicking on the green Load Sequence Annotation button under the Sequence & Gene Annotation menu. Note that some analyses can be performed in CoGe even when genome annotation data is not yet available. Also, any specific upload can be updated at any point in time. Thus, genome annotation data, metadata or experimental data can be included for a genome already imported into CoGe as soon as they become available.

- 10. The process to importing annotations is similar to that of importing genomes. Under the Describe your annotation page, select the version and source of the annotation data and click Next. As previously described, the data can be uploaded directly from the Cyverse Data Store, by creating a HTP/FTTP link, or by using the Upload option. Note that both GFF and GTF files can be used for uploading genome annotation data. Click Next and the annotation data associated to the genome will be imported onto CoGe. This information should now be visible on the Genome Information page under the Sequence & Gene Annotation menu (Figure 7). For more details about uploading genome annotations follow this link: LoadAnnotation

Exporting genomes from CoGe to Cyverse

- Data can be exported into Cyverse for easy sharing and storage after it has been imported onto CoGe. While this is not needed to use CoGe or perform any analyses, it is a highly recommended step for complete and Certified genomes (those which represent the latest and most complete version of a given species' genome up to date). You can use CoGe to export data into the CyVerse Data Store by following these steps:

- 1. While logged into CoGe, go to the Genome Information page on your genome of interest.

- 2. Under the Tools menu, find the Export to CyVerse Data Store option. Click either on the FASTA or the GFF file options to upload genomic data and its annotation, respectively. Make sure to specify a name for the GFF file before performing the export.

- 3. Wait until the export is completed. From this point forward, your FASTA and GFF files data will be also found in the CyVerse Data Store. Note that no modification can be performed to the uploaded genomes, so it is recommended to keep a list of the uploaded genome codes that is provided by CyVerse and their associated organism or strain.

Using CoGe tools to perform comparative analyses

Analyzing GC content and other genomic properties (GenomeList)

Comparative genomic studies have pointed out to significant variations on GC content between Plasmodium species and even amongst chromosomes. The average GC content of P. vivax and P. falciparum, two mayor causal agents of human malaria, is 42.3% and 19.4% respectively. In addition, the variation on GC content across chromosome regions has been known to vary between different species. Specifically, GC content has been shown to be particularly low on P. vivax subtelomeres, while regions of poor GC content are widespread across the entire P. falciparum genome [21]. The evolutionary origin of GC content change in Plasmodium has been a topic of interest for several years. It has been proposed that the Plasmodium common ancestor's genome might had been AT rich, a trait which has been maintained in P. falciparum, and consequently GC content has experience a reversal on consequently divergent Plasmodium species [22]. Alternatively, the AT richness observed in P. falciparum and closely related Plasmodium species might also be a synapomorphy unique to the ancestor of the Laveranian subgenus. Unfortunately, the current lack of Plasmodium genomes from clades ancestral to Laverania make difficult the evaluation of this hypothesis. Nonetheless, it is still possible to obtain a more complete perspective of GC content evolution within the genus thanks to the increasing number of sequenced Plasmodium genomes publicly available.

In CoGe, it is possible to easily calculate a genome's GC content by using the GenomeInfo tool found on Genome Information. By default, GC content will be displayed for genomes imported from GenBank; however, genomes uploaded from private computers or in earlier stages of assembly will not have the GC content information on display. In those instances where GC content is not displayed automatically, it is possible to perform the calculation on the Genome Information page itself. To calculate GC content, click on %GC under the Length and/or Noncoding sequence sections found on the Statistics tab.

In addition to on the go GC content calculations, it is also possible to compare and contrast GC content (and other genomic features), across several species/strains by using CoGe's tool called GenomeList. This tool creates a list including the genomes selected by the user and calculates various genomic features for each one. Among the features that can be comparative evaluated using GenomeList some of the most prominent are: amino acid usage, codon usage, CDS GC content, number of genes, and number of introns, etc. In addition, GenomeList also summarizes some of the metadata included by the user during genome import. This information includes: sequence type, sequence origin, taxonomy, provenance, version uploaded to CoGe, etc.

| The following steps indicate how to perform comparative analyses using the GenomeList tool in CoGe:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe 2. In the main CoGe page find the Tools tile and click on Organism View. You can also follow this link: https://genomevolution.org/coge/OrganismView.pl 3. Type the scientific name of the organism of interest on the Search box and select the desired version of the uploaded genome. 4. Find the Genome Information tile on the right side of the screen. Under Tools, find and click on Add to GenomeList. This will automatically generate a new window indicating that the selected genome has been added to a list. 5. Without closing this window, type the scientific name of other organisms of interest on the Search bar. Once you have selected your second genome, click on Add to GenomeList. The second selected organism should now appear on the same list. You can add as many genomes as desired (Figure 8). 6. Once you have included all genomes of interest click on the green Send to Genome list button. 7. After a couple of seconds, a new window showing a table including all your selected genomes will appear. Here you can select and compare the different genomic features of the selected genomes. Moreover, links to different types of calculations (e.g. amino acid composition, %AT, etc.) are provided for each included genome. In addition, while it is possible to perform specific analyses only certain genomes, you can also perform the same analysis for all GenomeList genomes by clicking on the green Get All found below each column's tittle. Depending on the number and quality of the included genomes, performing calculation on all genomes might take a couple of minutes. Also note that clicking on the Change Viewable Columns green button on the upper right part of the screen, allows the selection of the columns on display (Figure 9). 8. It is possible to download information from the selected genomes in various formats using "Send Selected Genomes to". Note that the information downloaded will correspond to the genomes themselves and not to the calculations and analyses performed on GenomeList.

|

We have used GenomeList to compare 12 Plasmodium species with completely sequenced genomes. Our results show that species closely related to P. falciparum share equally AT rich genomes. Moreover, GC content appears to gradually increase on Plasmodium clades thought to have diverged more recently (rodent and simian). Furthermore, more recently divergent species of the simian clade also show a continuous increment on GC content. P. vivax, P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi show the highest %GC out of all analyzed species with P. vivax surpassing these species by at least 6%. These results are in agreement with previous suggestions that GC content is currently undergoing a reversal on recently diverging Plasmodium species. It has been proposed that the increment of GC content in P. vivax, while maintaining poor GC content on subtelometic regions, might be indicative of an efficient genome organization [23]. Interestingly, GC content was markedly low on P. malariae (another causal agent of human malaria) when compared to other Plasmodium species of the simian clade. This result could suggest that P. malariae shares a similar GC content organization to that of Laveranian Plasmodium species. It should also be noted that none of the mayor human malarias showed identical levels of GC content; therefore, it is possible that GC content organization can be different across this group. It has been discussed that GC content has a fundamental role in the development and maintenance of variability within Plasmodium genomes; particularly, on antigenic variation [24]; however, this variation does not seem to be associated to host-specificity at a first glance. Furthermore, our initial results suggest that the mayor four human malarias might follow different evolutionary strategies in maintaining genome variability.

Identifying gene homologs (CoGeBlast)

Broadly speaking, different aspects of Plasmodium genome evolution can be observed in genes that belong to the Plasmodium core genome and those which are clade- or species-specific. Hence, there is no questioning that a significant step on comparative genomics, whether it is at a genome scale of in a group of genes, is the correct identification of homologous sequences. In this regard, the identification of multigene family members creates a particular challenge for the study of Plasmodium evolution. Multigene families are composed by genes with two different types of evolutionary relations: orthologs (homolog genes related to each other by speciation events), and paralogs (homolog genes related to each other by duplication events). Within the genus Plasmodium, multigene families perform a wide array of functions, showcase unique genome organization, and present diverse overall evolutionary patterns. While many families members are arranged in tandem and can be easily associated to the location of regions where microsynteny is loss, other multigene families are organized in far more complex patterns. Multigene families located on subtelomeric chromosome regions represent a particular challenge. Families located in these regions are commonly associated with important parasitic functions such as antigenic variation and immune evasion (var, stevor, rifin in P. falciparum and closely related species, and pir on P. vivax and closely related species), and thus are of particular interest in the study of human malaria. These complex families can include members distributed across different genome regions and even across different chromosomes; moreover, multigene family members have a tendency to undergo rapid sequence evolution, which poses unique challenges for the identification of ortholog/paralog relations. [25][26][27][28]

BLAST analyses allow the identification of family members based on sequence similarity scores and are of insurmountable importance in comparative genomics. However, the incorporation of easy visualization tools for the analysis of homolog regions between two or more genomes are likely to have a significant impact on the study of complex Plasmodium multigene families. We will use one of CoGe's tools (CoGeBlast) to identify multigene family members belonging to one of the more complex Plasmodium multigene families: vir [29][30]. We will also use this tool to find the location of BLAST hits across various Plasmodium genomes.

The vir super family is composed by 313 members [31]. Based on their sequence similarity, paralogs in the family can be grouped into 10 different subfamilies or remain independent [32]. Previous studies have found that less than a third of vir genes are found in more than one P. vivax strain, showcasing the rapid evolving nature of this family. Despite this variability however, 15 vir genes are shared across all five P. vivax strains currently sequenced. Moreover, the genetic diversity of these 15 genes was lower than that observed in other multigene family members. Within this small group, PVX_113230 presented the highest sequence similarity across strains and largely conserved synteny, suggesting a role as founder of the vir family [33]. PVX_113230 was used as an example of the functionality and features of CoGeBlast.

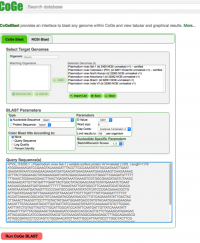

| The following steps show how to use theCoGeBlast tool in the CoGe platform:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe. 2. In the main CoGe page click on CoGeBlast under the Tools tile (Alternatively, you can follow this link: https://genomevolution.org/coge/CoGeBlast.pl). 3. Under Select Target Genomes, type the scientific name of your Organism of interest on the Search box. All organism and genomes with names matching the search term will appear under the Matching Organisms menu. Also, any Notebooks matching the term will appear in a new window named Import List. 4. Select all the organisms of interest by using Crtl+click or Command+click, and click on the green + Add button. The added organisms will appear on the Selected Genomes menu on the right. Alternatively, you can select any of the Notebooks found on Import List, and all genomes included in the Notebook will be automatically selected. 5. Copy the query sequence in FASTA format on the Query Sequence(s) section at the bottom of the screen. If desired, the BLAST analysis itself can be modified by changing the BLAST Parameters (Figure 10). 6. Once the analysis has been completed the output will include: a table showing the number of hits to the query sequence in the analyzed genomes, a graphic depiction of the location of these hits on the genome, and a list showing information for each hit including their similarity index.

|

In agreement with previously results, we found PVX_113230 to be highly conserved across P. vivax strains [34]. Interestingly, there was some small variation on the number of reported homologs across strains within the analyzed subfamily, with Mauritania, PO1, and the Salvador-1 showing the largest numbers of reported homologs. Our results suggest that even within relatively conserved family members, the vir superfamily is still highly diverse. Moreover, our analysis on the location of sequence hits between the P. vivax PO1 (not included on previous studies) and the Salvador-1 strains show highly conserved synteny between the two (Figure 11). A comparison between the two strains shows BLAST hits located in the approximate same chromosome positions unless absent. This pattern can also be observed, though in less detail, among the other analyzed P. vivax strains. Overall, our results suggest that while PVX_113230 indeed could be the founder of the vir superfamily, neighboring family members could have functions outside the stablished role on immune evasion. As expected, the number of BLAST hits and their chromosome location varied largely across P. vivax strains when a less conserved vir family member was used in the analysis.

Identifying microsyntenic regions (GEvo)

Inter and intra-specific patterns of genome evolution are often associated with genome rearrangements that result in loss of synteny. While large genome rearrangements are not prominent amongst closely related Plasmodium species, small rearrangements affecting specific portions of the genome or even just a few genes are commonly observed (Microsynteny). Within Plasmodium, microsynteny is usually lost in regions of high recombination frequency, sections where rapid gene turnover is evolutionary advantageous, or locations prone to gene gain/loss events. Therefore, changes in microsynteny are usually related to genomic regions of significant evolutionary interest. In species of the subgenus Laverania, significant loss of microsynteny has been observed in genes involved in parasite-host interaction; in particular, members of the reticulocyte-binding-like (RBL) family have displayed some unique evolutionary patterns. Members of the RBL family are essential for successful erythrocyte invasion, and are know to vary across Laveranian species. Two genes involved on erythrocyte invasion: the reticulocyte-binding-like homologous protein 5 or Rh5, and the cysteine-rich protective antigen or CyRPA have been recently thought to originate via an horizontal genome transfer (HGT) event early on the evolution of the subgenus, based on differences in their gene trees topology respect to that of the species tree [35]. In this section, we will use the CoGe tool: GEvo, to evaluate the properties of genome the region where Rh5 and CyRPA are located and search evidence of a potential HGT event. We will do this by visually representing evolutionary patterns in this region across multiple genomes.

| The following steps show how to use GEvo to analyze microsyntenic regions:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe. 2. Click on the GEvo tool on the main CoGe page (Alternatively, you can follow this link: (https://genomevolution.org/coge/GEvo.pl). 3. Each displayed box found under Sequence Submission allows you to select a sequence. You can specify as many as 25 sequences before performing a GEvo analysis. In each box you will find: a drop down menu of sequence databases (CoGe database, NCBI GenBank or Direct Submission), the name of the selected sequence (e.g. gene ID numbers), the length of genome segment to be displayed to the left and right of the sequence, and green button used to specify additional Sequence Options (skip sequence from the analysis, set sequence as reference, set sequence as reverse complement, or mask the sequence). You can import sequences for analysis by entering their gene IDs on the Name: bar. Alternatively, you can select pairs of genes for microsynteny directly from SynMap, either by zooming (SynMap2) or clicking (SynMap Legacy) on specific regions of the SynMap display. 4. Once you have selected your sequences, click on the red Run GEvo button. 5. The GEvo analysis will display the syntenic regions between the compared genome regions. Genes are shown in green at their genome location and syntenic genome are signaled as light colored red bars on top of each genome. You can connect syntenic regions between genomes by clicking on these bars. 6. The GEvo analysis itself can be modified by changing the parameters on the Algorithm tab. Also, you can modify the information of the graphical display by altering the options on the Results Visualization Options tab.

|

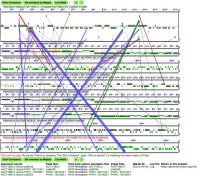

We searched for Rh5 orthologs in all fully sequenced Plasmodium genomes (P. falciparum strains 3D7 and IT, P. reichenowi strains CDC and SY57, and P. gaboni strain SY75) from the Laveranian subgenus by using CoGeBlast. We then used the provided output to perform a microsynteny analysis of these genome regions using GEvo. Our results show that microsynteny is largely maintained in the regions surrounding Rh5 and CyRPA; furthermore, there does not appear to be a marked difference in GC content inside and outside the region containing these genes for either of the evaluated genomes. It has been suggested that changes in GC content within any certain genome region that do not correspond to the background GC content, or to the GC wobble content of surrounding genes could be indicative of a HGT event (Figure 12). We modified the GEvo display to show variation on GC content and in wobble GC content. We did not observed any patterns suggesting a HGT event on either Rh5 and CyRPA, thus, our results do not support the previously suggested HGT event [36]. It is possible that an HGT event occurring between genomes of similar composition might not be detected by this analysis, and thus additional testing might be required in order to further support or reject this hypothesis. However, it should be noted that genes expressed during blood parasitic stages and involved on erythrocyte invasion, are expected to be largely affected by selective pressures imposed by the host's immune system [37], and thus, the differences in gene tree topology could be the results of factors not related to HGT events.

Alternatively, GEvo can be used to evaluate regions where synteny is loss in more detail. A synteny analysis between closely related Plasmodium species: P. vivax (Salvador-1 and PO1 strains) and P. cynomolgi (B-strain) shows an inversion event between P. vivax (Salvador-1), and P. vivax (PO1) and P. cynomolgi. A microsynteny analysis on the border regions where the inversion event is detected between shows a poorly sequenced region in the P. vivax Salvador-1 strain (Figure 13). Synteny is maintained ibetween P. cynomolgi and the P. vivax (PO1) is maintained in this region, but loss in P. vivax (Salvador-1). This suggest that the inversion event observed in P. vivax (Salvador-1) might be the product of the poorly sequencing genome segment.

Performing syntenic analyses between two genomes (SynMap)

One of the most important tools found in the CoGe platform is SynMap. This tool is used to identify syntenic ortholog genes between two genomes and provide a graphical output across the entire genome. Information obtained in SynMap is useful in identifying both highly conserved genome regions and sections where synteny has been loss, as well as to provide a starting point for the analysis of the events leading to loss of synteny (e.g. gene duplication events) and their consequences in genome evolution (e.g. neighboring gene effects on gene expression and transcription). There are two types of information which can be obtained by using SynMap:

| The following steps can be followed to perform comparative analyses using the SynMap tool on CoGe:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe 2. On the main CoGe page find the Tools section and click on Organism View (Alternatively, you can also follow this link: https://genomevolution.org/coge/OrganismView.pl) 3. Type the scientific name of a species on the Search box and select the appropriate genome. Then, click on the GenomeInfo link under the Genome Information section. 4. Find the link to the SynMap tool under the Analyze section on Tools. 5. By default, SynMap will allow you to evaluate the synteny of a genome with itself. This can be of used when characterizing a genome or when attempting to identify putative duplication events [38]. Alternatively, two different genomes or two different organisms can be analyzed by using. Genomes for Organism 1 or for Organism 2 can be selected by typing the species scientific name on the Search bar and then selecting the genome. Once you have selected both organisms run the analysis by clicking on Generate SynMap (Figure 14). 6. Once the analysis has been completed, SynMap will output a graphical depiction of the syntenic regions between the two genomes. There are currently two version of SynMap: the default version, SynMap2, allows the user to interact with the analysis and dynamically alter the output (e.g. zoom in into a particular region), and the older version, SynMap Legacy, which provides static images of the analysis. You can exchange between each version after performing the analysis. 7. Specific gene pairs of interest observed in SynMap can be analyzed in more detail in GEvo. The syntenic gene pair can be selected by zooming on the SynMap plot either by clicking on the region of interest on SynMap Legacy or by dragging the mouse over the region on SynMap2. GEvo can then be run for specific gene pairs by double clicking on their syntenic point (SynMap Legacy), or by selecting the point and clicking on Compare in GEvo >>> (SynMap2)

|

Identifying syntenic gene pairs

The variation on the number of gene pairs shared across any two genomes has clear implications on the maintenance of synteny across their genomes. Approximately, 1787 protein family members are shared between Plasmodium and Theileria [39] indicating that while many gene origins predate the split of these two genera and have been preserved, far more have origins after the split of both groups [40]. Within Plasmodium, the large number of newly sequenced genomes allows to identify the potential point of origin of many Plasmodium-specific genes, as well as to infer the role that these genes might have on creating positional changes between genomes. It is possible that changes in the sequence of genes in a genome affect the neighboring sequences where new genes are introduced or lost. Previous studies have shown that gene expression and transcriptome evolution are affected by genome position [41][42]. Specifically within eukaryotes, gene expression and gene regulation is largely dependent on genome location and gene co-expression clusters have a significant role in eukaryotic gene regulation [43]. While there are comparative less studies that evaluate potential relations between gene co-expression and genomic location in Plasmodium, there is evidence that certain genes are strictly up-regulated during specific parasite life stages [44]. Therefore, using newly sequenced Plasmodium to analyze syntenic gene pairs across different paired genome combinations, provide a unique opportunity to identify functionally advantageous clusters preserved by natural selection, and to determine the role of gene order could on gene expression within the genus.

Identifying chromosomal inversions, fusions, fissions and other events between two genomes

Genome rearrangement events can also be identified using SynMap. Rearrangements originate when genome regions are duplicated, loss, inverted, or when fusion or fission events occur. The identification of these events can pinpoint to regions of rapid change in a genome or to infer the evolutionary origins of certain genomic elements.

Initial studies evaluating genome architecture across species from the phylum Apicomplexa have shown that while synteny amongst genera is loss for the most part, gene order and position is largely maintained within Plasmodium. Nonetheless, as a larger number of Plasmodium genomes becomes available, is apparent that synteny patterns within the genus are far more complex than previously thought. With the exception of certain genome regions, closely related Plasmodium species have largely syntenic genomes; on the other hand, numerous rearrangement events are observed in more divergent species form different Plasmodium clades [45]. Thanks to the larger number of Plasmodium genomes currently available, it is possible to evaluate synteny within the genus in a more complex array of species. By performing several paired comparisons across different species sets is possible to estimate the origin of many species-specific genomic rearrangements events and assess their significance on genome evolution.

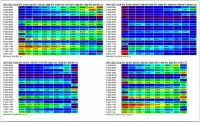

In the case of P. vivax and closely related species, loss of synteny events between P. vivax, P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi have been reported on chromosomes 3 and 6. An analysis of these species using SynMap shows inversion events between P. vivax and both P. knowlesi and P. cynomolgi. Nonetheless, no inversion events are observed between P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi. This suggest that the chromosomal inversions reported for chromosomes 3 and 6 might have occurred after the split of P. cynomolgi and P. vivax (approximately between 3.43-3.87 Mya) and can be unique of the P. vivax genome [46]. SynMap can also be used to identify sets of chromosome fusion/fission events unique to specific genomes. Pairwise comparisons between the genomes of four closely related Plasmodium parasites: P. ovale curtisi, P. malariae, P. coatneyi and P. knowlesi; show that at least two sets of inversions and fusions have occurred in the P. coatneyi and P. malariae genomes. SynMap results show two fusion events in chromosomes 5 and 9 unique to P. malariae (Figure 15 and 16, marked with red squares) and two additional fusion events in chromosomes 13 and 14 of P. coatneyi (Figure 15 and 16, marked with green squares). Also, and inversion event can be observed in the central region of chromosome 4 in P. malariae (Figure 15 and 16, marked with a blue circle).

Measuring Kn/Ks values between genomes (SynMap - CodeML analysis tool)

After the point of divergence, differences in nucleotide loci will accumulate between two genomes as the result of evolution, the nature of the accumulated changes can be assessed by comparing the homologous coding sequences across these genomes. Nucleotide changes that do not affect the coded amino acid are called synonymous, while those changes that result on a difference amino acid are called non-synonymous. Synonymous substitutions are largely neutral and reflect the background evolutionary changes of a genome; thus, they are often used to determine genome's mutability and to establish the relative age of genome rearrangement events. Alternatively, non-synonymous substitutions are largely affected by natural selection, and produce either positive or negative changes. As such, the Kn/Ks ratio provides a picture of some evolutionary forces shaping gene evolution by measuring the rate of efficient changes respect to those on the background. Under neutrality it is expected that synonymous and non-synonymous changes will occur at the same rate (Kn/Ks = 1), when non-synonymous substitutions are fixated at a faster rate than synonymous ones Kn/Ks > 1 indicating positive selection, and when the rate of fixation of amino acid changes is reduced by new amino acid changes being eliminated Kn/Ks < 1 indicating purifying selection. While other software can calculate Ks, Kn and Kn/Ks values across numerous genes, the CoGe platform has the unique capability of calculating the Ks, Kn and Kn/Ks ratio on syntenic gene pairs across the whole genome. Thus, CoGe's Ks, Kn and Kn/Ks analyses are used to: determine the role of natural selection in relation to the relative position of syntenic gene pairs between two genomes, define genome regions which evolve under different selective regimes in relation to the predominant trends seen on the rest of the genome, identify the relative age of genome rearrangement events (e.g. duplications), and establish genome-specific trends in evolution (e.g. rapid evolving genomes respect to their sister taxa). In parasites of the genus Plasmodium, differences in evolutionary rates across genome pairs can be indicative of species- or genus-specific adaptive trends, the product of parasite-hosts interactions, or the result of differences between genome properties. Overall, the analysis of these variations across the genus is fundamental in understanding of its evolutionary trends.

In the CoGe platform, Kn/Ks analyses can be performed for two annotated genomes after a SynMap analysis has been completed. The output analysis will modify the Syntenic_dotplot display to represent the distribution of the different Ks, Kn or Kn/Ks ratio across syntenic pairs.

| The following steps show how to perform Kn/Ks analyses using the CodeML tool available on SynMap:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe. 2. Perform a SynMap analysis between two genomes. CoGe has the capacity to store all analyses performed under a users' account, so previously generated SynMap analyses are available for further testing down the line. Note that regardless on their levels of assembly, Ks, Kn, and Kn/Ks ratios can only be calculated for annotated genomes (genomes with imported .gff files). 3. Once SynMap has been generated, find the CodeML tool under the Analysis Options tab at the bottom of the screen. Click on the Calculate syntenic CDS pairs and color dots:________ substitution rates(s) section and select Synonymous (Ks) from the dropdown menu. You can repeat the analyses by selecting the: Non-synonymous (Kn) and (Ks/Kn) options. The display can be modified by choosing a different Color Scheme, specifying the axis default Min Val. or Max Val., or by changing the Log10 Transform. data options. 4. The resulting output will display the distribution of Ks values (or Kn or Ks/Kn) across the syntenic regions between the two evaluated genomes. In addition, the output will include a Histogram of Ks values (or Kn or Ks/Kn). In SynMap2, specific regions/chromosomes can be dynamically selected to view the Ks, Kn or Ks/Kn values in that region.

|

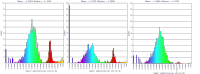

Smaller Log10 substitution per site values are indicative of a lower number of synonymous (Ks) or non-synonymous (Kn) substitution. Since the effects of Natural Selection on synonymous substitutions is thought to be minimal, they are expected to accumulate in a largely constant manner. Paired Ks analyses performed between different genome sets provide information regarding the divergence and background selection between genomes. Our Ks analyses results between P. gaboni (SY57) and P. reichenowi (CDC) show a larger number of recent synonymous substitution compared to P. gaboni - P. falciparum (3D7) (Figure 17). This is interesting since, P. reichenowi and P. falciparum have a more recent divergence time (approximately 5.28-5.93 Mya [47]), than with P. gaboni with whom they both share a distant common ancestor [48]. The different Ks rates in P. falciparum and P. reichenowi respect to P. gaboni, suggest that a change in the rate of synonymous substitution occurred after the split of P. reichenowi and P. falciparum, since changes occurring in their common ancestor would reflect higher similarities on synonymous substitutions in comparisons to the more ancestral P. gaboni. Additionally, the Ks values between P. reichenowi - P. falciparum are slightly smaller than those observed between P. falciparum - P. gaboni suggesting that Ks rates have increased uniquely in P. reichenowi. Our results indicate that syntenic P. reichenowi genes are evolving at a more rapid rate than other species within the Laveranian subgenus.

Alternatively, the pattern of non-synonymous (Kn) substitution observed between P. gaboni - P. falciparum and P. gaboni - P. reichenowi are largely similar (Figure 18) suggesting that a comparable number of non-synonymous substitutions occurred after the split of P. reichenowi and P. falciparum common ancestor from P. gaboni. Moreover, the smaller rate but more recent number of non-synonymous substitutions observed between P. falciparum - P. reichenowi indicates that a number of non-synonymous substitutions are unique for each species. These results show that natural selection, and likely host-parasite interactions between different host types, has had a significant role in shaping the evolution of Laveranian genomes.

Previous studies have shown that non-synonymous substitution rates are particularly large in a significant number of ortholog sequences between P. reichenowi and P. falciparum, with selective pressures and gene gain/loss events being largely predominant during blood stages of the parasite's life cycle [49]. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that P. falciparum colonization of humans might have also been facilitated by genome transfer of several key erythrocyte invasion proteins [50]. Our results support the observation that natural selection, and likely host-parasite interactions, have a significant role on the evolutionary trends observed in Laveranian; however, intrinsically different rates of background selection are predominant on P. reichenowi vs. P. falciparum, advising a need to account for this variation on future evolutionary studies.

Identifying sets of syntenic genes amongst several genomes (SynFind)

A significant level of genome rearrangements is prevalent between Plasmodium clades and even within species inside a single clade. A large number of the events leading to loss of synteny are associated to species-specific gene gains/loss, many of which, result on homologous genes becoming scattered across different genome regions. In this regard, it is of great significance to use tools that permit the identification of syntenic regions across genomes, and in particular, of regions where complex evolutionary patterns might be observed. The identification of these regions, more than that of particular genes itself, can provide indispensable clues regarding the evolutionary origin and trajectory of specific genome segments. Within Plasmodium, characterizing syntenic regions where multigene family members are found can aid in the identification of gain/loss events that might remain otherwise undetected and also in determining potential rearrangements of the family's organization. Moreover, focusing on syntenic regions in lieu of syntenic genes alone allows the assessment of non-coding sequences as well, which can provide clues on the patterns of gene family expansion, contraction, rearrangement, and the overall evolutionary history of specific chromosome segments. Evolutionary changes in syntenic region (coding and non-coding) are readily detected where multigene families with tandem chromosome arrangement are located; thus, we will use the Plasmodium SERA (serine repeat antigen) multigene family to evaluate these patterns.

SERA multigene family members encode proteins with a papain-like cysteine protease motif [51], and are expressed during various stages of the Plasmodium life cycle. One member of this family (SERA-5) is produced during late trophozoite and schizont stages, and has been a widely considered as a promising malaria vaccine target currently on phase Ib clinical trial (studies conducted in diagnosed patients) [52]. While members of the SERA family have been described in all sequenced Plasmodium genomes, the family has experienced a significant amount of contractions, expansions and rearrangements across Plasmodium species. These variation pinpoints to a highly dynamic evolutionary history. Here, we will use CoGe's SynFind tool to characterize the syntenic regions across a set of genomes in reference to a specific query gene and reference genome.

| These steps show how to use SynFind to search for syntenic regions associated to particular sets of genes from a reference genome:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe. 2. On the main CoGe page find and click the SynFind tools tile (Alternatively, you can follow this link: (https://genomevolution.org/CoGe/SynFind.pl). 3. Type the scientific name of your desired organism on the search bar under the Search tab on the Select Target Genomes section. Organisms and genomes with names matching the search term will be displayed on the Matching Organisms menu. 4. Select all the genomes of interest using Crtl+click or Command+click. After you have selected all genomes of interest click on the green + Add button and the added genomes will appear on the Selected Genomes menu on the right. 5. Type the Name, Annotation or Organisms of interest in the Specify Features section. It is recommended to provide as many specifics for this query as possible; nonetheless, the analysis can be performed even with less specific terms (e.g. it is possible to retrieve the sequences of interest just by typing "sera" on the Name box). Once you have specified the features click on the green Search button. 6. All matches to the search term, and the genome where they have been found, will appear in new menu within the same section. Select all relevant Matches (e.g. all SERA genes) and your reference Genome (e.g. P. falciparum strain 3D7 v5). 7. Click the red Run SynFind button to start the analysis. 8. SynFind will output all syntenic regions to the query sequence found on the reference genome and their Syntenic depth. Using this output, sequences can be further analyzed with any of the tools available on CoGe (generate SynMap dotplots, perform a microsynteny analysis with GEvo, etc.).

|

We used Synfind to identify potential syntenic regions to SERA-5 across six P. vivax strains from different geographic regions. The information provided by SynFind allows the rapid identification of regions where multigene family members are found which can be later characterized in more detail with GEvo. Our results show that all evaluated P. vivax strains share the 12 reported SERA paralogs [53]; however, there is some intraspecific variation between the syntenic regions where SERA paralogs are found. Specifically, synteny is loss on certain family members on the P. vivax Brazil-1 strain (Figure 19, shown as second from the upper part of the screen). The regions where synteny is loss are associated with the location of paralogs uniquely found in P. vivax and closely related species. Therefore, it is possible that recently duplicated paralogs might have not yet been fixated at the intraspecific level, or that there are certain evolutionary advantages associated with a variable number of paralogs within the same species as previously discussed for other Plasmodium multigene families [54]. It should be noted however that multigene family members are characterized by a family common motifs which can be occasionally found in genes non related to the family itself. Therefore, motifs and domains identified by SynFind should be carefully evaluated before reaching conclusions about their role in sequence's evolution (Figure 20, shows a conserved motif shared by non member of the SERA family).

Identifying codon and amino acid substitution frequencies (CodeOn)

The significance of compositional bias on codon and amino acid usage within the genus Plasmodium has been previously highlighted. Within P. falciparum, compositional bias has been associated with variations on codon usage and gene expression; specifically, a preference for C-ended codons has been observed in many highly-expressed genes despite the parasites' AT rich genome. Expression patterns have also been associated to the usage of less energetically expensive amino acids, which could suggest that there is an evolutionary advantage on decreasing energetic costs during infection by translational selection [55]. The significance of compositional bias and translational selection is largely variable on other Plasmodium species; in particular, translational selection has been shown to have a small, yet higher than P. falciparum, role on codon usage bias on P.vivax [56]. With the large number of Plasmodium genomes currently available and the significant compositional bias observed within the genus, it is relevant to identify potential differences in codon and amino acid usage amongst Plasmodium species.

The role of compositional bias has been evaluated on 6 Plasmodium species representing three of the four mayor Plasmodium clades (Laveranian, simian and rodent). Currently, the large number of Plasmodium genome sequenced allow us to assess the role of composition bias on closely related species which similar nucleotide composition as well as between more divergent ones. We will use CoGe's analysis tool named CodeOn to assess the differences in codon and amino acid usage across Plasmodium species and their potential relation with variation on GC content. The CodeOn tool calculates amino acid usage across various levels of %GC and the number of CDS under the computed %GC tiers.

| The following steps indicate how to built amino acid usage tables for any given genome:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe. 2. Find the organism and genome of interest in Organism View (https://genomevolution.org/coge/OrganismView.pl). 3. Find the Genome Information section on the right side of the screen. Find the CodeOn tool under Tools and click to start the analysis. After a couple of minutes, the analysis output will be shown in a different tab. |

As expected, similarities on %GC were more prevalent amongst closely related species than species from different Plasmodium clades (Figure 21). Within the simian clade, P. vivax showed a large number of CDS with 45-55% GC, while other species presented a slightly more skewed 40-45% GC on most CDS. Alternatively, Plasmodium species of the Laveranian subgenus showed a larger number of CDS with a reduced 20-30% GC. Nonetheless, CodeOn results show that the patterns of amino acid usage in relation to the variations on GC content are still unique for each Plasmodium species. Interestingly, P. vivax and P. coatneyi showed higher similarities in amino acid usage than with their respective sister taxa (P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi, respectively). These differences do not appear to be solely related to composition genome bias, since in both cases GC content is more similar amongst sister taxa. Our results suggest that amino acid and codon usage are likely influenced by forces beside compositional bias in Plasmodium species from the simian clade. Taking into account previously reported associations of codon usage and translational selection on P. vivax, it would be relevant to explore if similar patterns are observed in other of the newly sequenced Plasmodium genomes.

In the case of Plasmodium species from the Laveranian subgenus, the sister species P. falciparum and P. reichenowi showed both similar amino acid usage, and number of CDS under low %GC tiers (Figure 22). On the other hand, P. gaboni showed similar %GC patterns but dissimilar trends in amino acid composition. The likeness in the patterns observed among Laveranian species confirms that compositional bias is a significant factor on determining amino acid usage within the subgenus; however, and similarly to species on the simian clade, additional elements also appear to play a role in determining amino acid usage and composition. While difficult to assess using only three representative genomes, it is possible that the changes in amino acid usage might have originated in specific points during the diversification of the Laveranian subgenus; specifically, the skewed amino acid usage observed on P. reichenowi, and more predominantly on P. falciparum, could represent a recently derived trait associated to the infection of different host types which could have originated after their split from P. gaboni.

Using Syntenic Path Assembly (SPA) to make analysis of poor or early genome assemblies easier (SynMap - SPA tool)

While in recent years the Plasmodium genome panorama has become more complete, there are still a large number of Plasmodium genomes that remain to be fully sequences, assembled and annotated. Incomplete genomic data originates from a variety of sources: poorly sequenced or assembled genomes, published genomic information in its earlier stages of assembly, partially sequenced genomes, and unassembled private genomes. One of the many challenges for the sequencing and assembly of Plasmodium genomes is the number of repetitive elements, low complexity sequences, and multigene families which vary largely between Plasmodium species and even among chromosome regions. Therefore, even with the use of reference genomes and the widespread usage of novel sequencing techniques, the assembly of Plasmodium genomes can be a complex task [57]. While unassembled genomes can be used in multiple types of studies (e.g. calculating the polymorphism on specific genes or genome regions, analysis of specific sets of genes, etc.), the information that they provide in genome level comparative genomics analyses can be limited.

Hereof, tools capable of quickly generating preliminary genome assemblies and finding syntenic orthologs to a reference genome can allow the identification of genome elements of interest. One of CoGe tools, the Syntenic_path_assembly or SPA, generates a quick genome assembly for any non-assembled genome using any selected reference genome. With this tool, it is possible to obtain and graphically display information regarding syntenic gene pairs between two genomes; alternatively, SPA can also be used to correctly orient syntenic regions annotated using reverse DNA strands. We will use the SPA tool to assemble the P. inui genome (currently on scaffold level) against the assembled P. coatneyi genome.

| The following steps shows how to use the SPA tool found in SynMap:

1. Go to: https://genomevolution.org/coge/ and login into CoGe 2. Run a SynMap analysis between an assembled genome and a non-assembled one (this might longer than analyses between two fully assembled genomes). 3. Once SynMap has been generated go to the Display Options tab and find the SPA tool (Figure 23). Select the tool by clicking on the check mark next to: The Syntenic Path Assembly (SPA)? 4. After a few minutes (depending of the number of contigs) the incomplete genome will be assembled using the second genome as a reference.

|

While syntenic regions between the two genomes can be characterized to a certain degree using SPA, there are some significant limitations regarding assembly interpretation using this tool. For one, the incomplete genome will be assembled using any provided reference; and thus, non-assembled contigs will be arranged in a way that allows the largest possible synteny between the incomplete genome and the reference. As a result, the assembly might not be the same when different reference genomes are used. In the case of P. inui, SPA can be run using P. coatneyi (a closely related species) or P. falciparum (a species from the Laveranian subgenus) as a reference. In either case, synteny of the non-assembled genome will be maximized, even though significant rearrangement events are known to have occurred between P. coatneyi and P. falciparum. Therefore, SPA reference genomes should be selected after careful consideration of the biological and evolutionary relation between species, and the results should be assessed with caution. Another aspect to look put for when using the SynMap SPA tool is the identification of rearrangement events, such as inversions or duplications, between genomes. Various contigs can potentially be syntenic to a same region or the reference genome and without proper care they can be incorrectly identified as a duplication events; on the other hand, contigs could have been annotated using a reverse DNA strand and be incorrectly identified as an inversion. Both potentially misinterpreted scenarios are shown in the SPA assembly of P. inui using the P. coatneyi genome as reference (Figure 24, events are indicated with black circles)

Overall conclusions

The number of available Plasmodium genomes has increased markedly during recent years. This increate of genomic information creates an unprecedented opportunity for the study of the unique qualities observed on Plasmodium genomes and to understand evolutionary patterns shaping this genus. Comparative analyses of Plasmodium genomes with different levels of relation allow for a better understanding of the origin, nature and predominance of these evolutionary forces.

Thanks to worldwide efforts, there has been a large reductions in the number of malaria cases and deaths between 2000 and 2015. By 2015, it was estimated that the number of malaria cases had decreased from 262 million to 214 million, and the number of malaria related deaths from 839,000 to 438,000 [58]. While this is an enormous achievement for malaria treatment and control strategies, there are still numerous aspects which need to be fully understood in the study of malaria and of the Plasmodium parasite itself. Human infectious of P. cynomolgi [59] and P. knowlesi [60] have been reported on SouthEast Asia. Also, various Plasmodium species from the Laveranian subgenus, including P. falciparum strains, have been found in African primates [61][62] suggesting a potential role of wild primates as malaria reservoirs. Both cases illustrate the plasticity of the Plasmodium genome and shown how feeble species barriers and host-specificity can be within the genus. In consequence, molecular studies on Plasmodium would highly benefit from a genus level approach instead of a more limited species-specific one; moreover, the implementation of tools which permit the straightforward assessment of genome levels trends across the genus is imperative. Thus, the use of platforms like CoGe, where genomes can be easily imported, analyzed, visualized and made public represents an essential step in furthering comparative genomes in the genus Plasmodium.

Here we demonstrated how different tools available on CoGe can be used to successfully test a number of hypotheses and patterns relevant in understanding Plasmodium genome evolution. We have also used this platform to further characterize both general and specific genome elements on sequenced Plasmodium species and strains. Regardless, the present study is not without its limitations given the lack of fully sequenced non-mammal Plasmodium species. In order to illustrate a more complete panorama on the complex evolutionary history in this genus, genomes from Plasmodium species ancestral to the Laveranian subgenus will be required. Evolutionary questions such as the origins on the AT richness observed in the Laveranian subgenus, the potential changes in synteny between mammal and non-mammal infecting Plasmodium species, the role of genome elements in the development of host-specificity and in virulence, and the expansion/contraction/origin of multigene families can be more clearly evaluated once these genomes are available. When this time comes, their incorporation into the CoGe platform and consequent analysis using CoGe's tools will aid in the evaluations of these hypothesis. Overall, our results show that the complexities of the Plasmodium genome can be effectively analyzed in CoGe, and that by doing this, more opportunities for furthering our understanding of malaria evolution are opened.

Useful links

Plasmodium Notebooks in CoGe

- Link to Notebook for published Plasmodium genome data: https://genomevolution.org/coge/NotebookView.pl?lid=1753

- Link to Notebook for published P. falciparum strains: https://genomevolution.org/coge/NotebookView.pl?lid=1758

- Link to Notebook for published P. vivax strains: https://genomevolution.org/coge/NotebookView.pl?lid=1760

- Link to Notebook for published Plasmodium apicoplast data: https://genomevolution.org/coge/NotebookView.pl?lid=1754

- Link to Notebook for published Plasmodium mitochondrion data: https://genomevolution.org/coge/NotebookView.pl?lid=1756

Sample data

- Gene sequence used on CoGeBlast analysis (obtained from PlasmoDB):

- PVX_003830.1 | Plasmodium vivax Sal-1 | serine-repeat antigen 5 (SERA) (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo/app/record/gene/PVX_003830)

- Gene sequences used on CoGeBlast used to inform GEvo analysis (obtained from PlasmoDB):

- PF3D7_0424100.1 | Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 | reticulocyte binding protein homologue 5 (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo/app/record/gene/PF3D7_0424100)

- PVX_096410.1 | Plasmodium vivax Sal-1 | cysteine repeat modular protein 2, putative (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo/app/record/gene/PVX_096410)

References

- ↑ Jackson AP. 2015. Preface. The evolution of parasite genomes and the origins of parasitism. Parasitology. 142 Suppl 1:S1-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25656359

- ↑ Carlton JM, Perkins SL, Deitsch KW. 2013. Malaria Parasites. Caister Academic Press

- ↑ Tachibana SI, Sullivan SA, Kawai S, Nakamura S, Kim HR, Goto N, Arisue N, Palacpac NM, Honma H, Yagi M, Tougan T, Katakai Y, Kaneko O, Mita T, Kita K, Yasutomi Y, Sutton PL, Shakhbatyan R, Horii T, Yasunaga T, Barnwell JB, Escalante AA, Carlton JM, Tanabe K. 2012. Plasmodium cynomolgi genome sequences provide insight into Plasmodium vivax and the monkey malaria clade. Nat Genet. 44: 1051–1055. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3759362/

- ↑ Prugnolle F, Durand P, Ollomo B, Duval L, Ariey F, Arnathau C, Gonzalez JP, Leroy E, Renaud F. 2011. A Fresh Look at the Origin of Plasmodium falciparum, the Most Malignant Malaria Agent. PLoS Pathog. 7: e1001283. http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1001283

- ↑ Prugnolle F, Rougeron V, Becquart P, Berry A, Makanga B, Rahola N, Arnathau C, Ngoubangoye B, Menard S, Willaume E, Ayala FJ, Fontenille D, Ollomo B, Durand P, Paupy C, Renaud F. 2013. Diversity, host switching and evolution of Plasmodium vivax infecting African great apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:8123-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23637341

- ↑ DeBarry JD, Kissinger JC. 2011. Jumbled Genomes: Missing Apicomplexan Synteny. Mol Biol Evol. 2011 Oct; 28(10): 2855–2871. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176833/

- ↑ Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, Mbogo CM, Hemingway J, Patil AP, Temperley WH, Gething PW, Kabaria CW, Burkot TR, Harbach RE, Hay SI. 2012. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors. 5:69. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22475528

- ↑ Buscaglia CA, Kissinger JC, Agüero F. 2015. Neglected Tropical Diseases in the Post-Genomic Era. Trends Genet. 31:539-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26450337

- ↑ Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. 2016. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 44: D67–D72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4702903/

- ↑ Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, Gingle A, Grant G, Harb OS, Heiges M, Innamorato F, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Kraemer E, Li W, Miller JA, Nayak V, Pennington C, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Ross C, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Treatman C, Wang H. 2009. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D539-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18957442

- ↑ Logan-Klumpler FJ, De Silva N, Boehme U, Rogers MB, Velarde G, McQuillan JA, Carver T, Aslett M, Olsen C, Subramanian S, Phan I, Farris C, Mitra S, Ramasamy G, Wang H, Tivey A, Jackson A, Houston R, Parkhill J, Holden M, Harb OS, Brunk BP, Myler PJ, Roos D, Carrington M, Smith DF, Hertz-Fowler C, Berriman M. 2012. GeneDB--an annotation database for pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:D98-108. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22116062

- ↑ Bensch S, Hellgren O, Pérez-Tris J. 2009. MalAvi: a public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol Ecol Resour. 9:1353-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21564906

- ↑ Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan MS, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DM, Fairlamb AH, Fraunholz MJ, Roos DS, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Cummings LM, Subramanian GM, Mungall C, Venter JC, Carucci DJ, Hoffman SL, Newbold C, Davis RW, Fraser CM, Barrell B. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 419:498-511